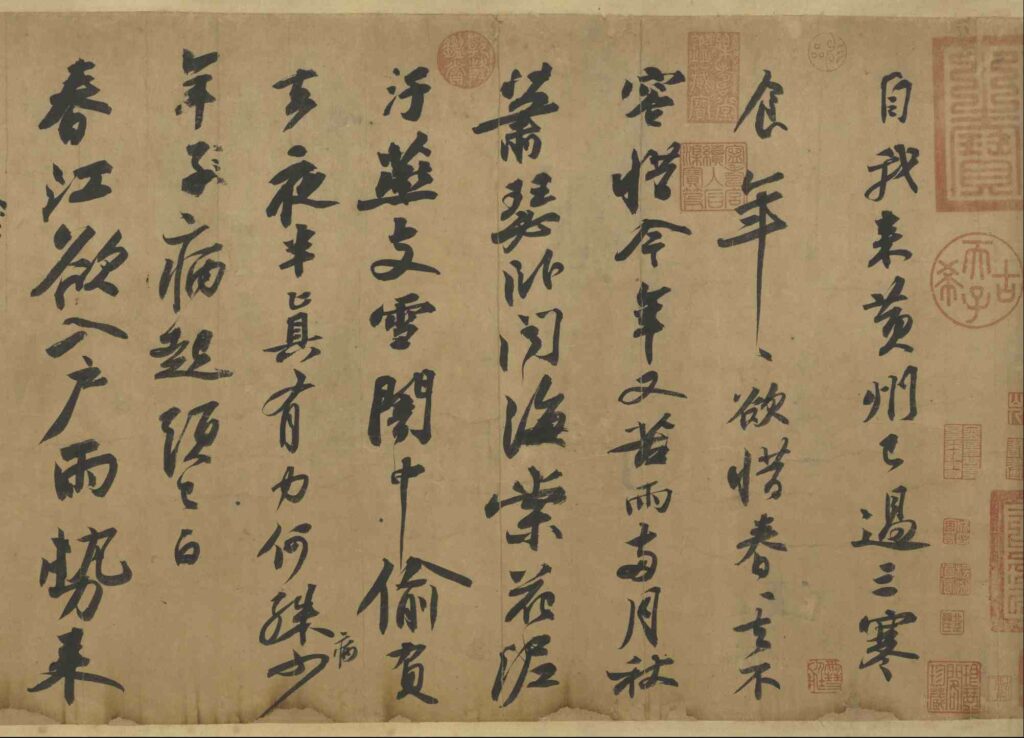

“Cold Food Observance Manuscript” (寒食帖) by Su Shi: A Masterpiece of Cursive Anguish

Introduction: Tears on Paper

Why This Matters:

In 1082, exiled poet Su Shi created what’s now called “China’s third greatest cursive script“ – not with perfect brushstrokes, but with wine-stained paper and shaky handwriting. This is art born from political persecution.

Key Terms:

- Cold Food Festival: Ancient Chinese holiday (no cooking, only cold meals)

- Huangzhou Exile: Su Shi‘s 4-year banishment after false accusations

I. The Manuscript as a Time Machine

Physical Details That Speak

| Feature | Significance | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Patchy Paper | Made from hemp – coarse and uneven | Like writing on crumpled notebook paper |

| Wine Stains | Infrared scans show alcohol in ink | Whiskey spilled on a legal document |

| Changed Words | “Cry” scribbled over into “Bitter” | Editing a tweet to sound less emotional |

Interactive Element:

[Before/After Slider] Compare clean calligraphy vs. Su Shi‘s distressed strokes

II. Decoding the Brushstrokes

A. Su Shi’s Handwriting Analysis

- Tight Clusters → Panic attacks

- Characters jammed together like subway riders in rain

- Flying White (Dry Brush) → Running out of ink (and hope)

- Like a pen dying mid-sentence

B. The 3 Emotional Sections of Cold Food Observance Manuscript

- Opening: Steady strokes – “I came to Huangzhou…” (pretending to be fine)

- Middle: Ink splatters – “Cold food, cold vegetables…” (hunger pains)

- End: Faint traces – “Deep gates of the emperor…” (exhausted resignation)

III. Why Art Historians Obsess Over This

1. The “Imperfect” Revolution

- Broke calligraphy rules:

✅ Traditional: Balanced spacing

❌ Su Shi: Words crashing into each other like drunk friends

2. The Hidden Su Shi‘s Self-Portrait

- “Broken Stove” character:

- Top part collapsing → His ruined career

- Bottom strokes thrusting upward → Defiant creativity